Cars:

Here’s a sample, the first two paragraphs:

No one had entered The Aberdares National Park by the east entrance in three days, as we found on signing in. We had just driven up from Nyeri in Kenya’s central highlands in our Hertz Land Rover. The drive had been thrillingly Kenyan. In Nyeri an industrious shade-tree mechanic there had looked at the noisy drive train and cheerily announced,

“There’s nothing wrong except your propeller shaft is about to fall off. Nothing serious.”

He went off to borrow tools and get pieces welded. To boot, he had the throttle linkage welded, having found a kink in it about to break. So, we felt reasonably confident in the mechanical integrity of Zebra Bones, as we called it – or as confident as one could be in a Land Rover in that day; “The Gods Must Be Crazy” brings us a flood of pangs of recognition with its hilarity. We were on small, unpaved roads, engulfed in the sights, sounds, and humic smells, feeling so close to the Earth, the culture, the nature of the country.

Food memories

Here’s the start:

We travel for scenery, people, cultures, wildlife; food is never a consideration in our choices, but it certainly “happens.” Here are some of the highs, lows, and amusing interludes in 41 countries.

Chinese seafood soup in Tolanaro, far southestern Madagascar. So delicious! Our son, David, age 5, and I would scramble to divide up the bowl. The ambience was also superb – the middle of nowhere, almost, with a sweeping view of a beach

Ikan rica rica – picture a spiced whole fish, sprinkled in pepper, brown and red – at Tirta Gangga, Bali. We had just finished walking around the water temple. The waiter presented the fish to me as we sat outdoors in the late afternoon.

The French:

Again, the beginning:

It’s July of 2003. We’re sitting on the shuttle bus from the off-airport hotel to Charles de Gaulle airport, anticipating our trip on the ultra-high-speed train, the TGV, to Montpellier in the South.

I’d just admonished our son, David, and his girlfriend, Sachi, to be on time. Before we left the US, I’d bought the tickets on the SNCF website for an amazing 25 euros apiece, but if we missed the train, I’d have to buy new tickets for as much as $400 equivalent. I shuffled through the printouts of the tickets and turned, ashen, to Lou Ellen, my wife. I hadn’t checked the tickets in months. The train I’d booked was leaving not from the airport but from the Gare de Lyon in the city center. No way to get there on time!

Greatly abashed and disheartened, I walked around the train station in the airport, encountering two itinerant agents. I showed them the tickets and, in my still-fluent French, I ask them about our options. “Desolee, monsieur…nonechangeable, nonremboursable, …” Fears fully confirmed, I got in line to see the ticket agent. In a few minutes, I reached the young man. ”’Tickets in hand, I told him that we needed new tickets. In French, for both of use wer very comfortable in it, he asked, “Est-ce que votre avion etait en retard?” “Was your plane late?” No, I explained; I just misread the tickets. He got to work finding another train. Soon, he turned the computer screen to show me the new reservation, and the still startling cost, now 400 euros, $500. With a sigh, I handed him my credit card. He demurred, and got to work again. This time he showed me another connection. We’ll take the train to Lyon, have a five-hour layover (time for some good food!), and catch another TGV to Montpellier. “C’est combien?,” I ask. “Gratuit,” he answers. He wrote it up as if our plane had been late, saving us the entire cost! I left elated, and then jumped back quickly to shake his hand and to say, “ C’est pourquoi j’aime les francais! We were on our way soon, cruising at 250 kph, about 150 mph, on the silky smooth run.

Bob From Bamenda

As Shelley explained to us that warm evening in the eastern jungles of Cameroon, the true “world traveller” comes unannounced:

“Hi, I’m Joe. Bob from Bamenda said I could stay with you.”

You don’t know this person, nor can you recall ever meeting a Bob from Bamenda. Still, you’ve received hospitality in unexpected quarters, so you reciprocate, in this oblique manner, by putting up this traveler with his or her knapsack full of a few possessions. Travel tales are the main compensation, and often they’re quite adequate. Tales shared in several languages can be most intriguing. Still at Shelley’s house, we were joined by other Peace Corps volunteers like herself, as well as by French Volunteers. As a courtesy to the French and to French being the language of this part of Cameroon, we all switched to French. As the conversation got deeper and livelier, we began dropping out, one by one. Finally, among the Americans only Peter, who had been there longest, hung in. The rest of us, hors-de-combat, listened appreciatively as Maurice constructed more and more complicated discussions and Peter responded authoritatively. At length, Maurice strung together a slew of compound sentences with vaguely

familiar grammatical constructions. Peter listened thoughtfully and responded with a sage “peut-etre.” “Well done,” we all thought to ourselves. Only later did Peter tell us that he hadn’t the faintest idea what Maurice was talking about. Taking his cue from inflection, he chose the safe “could be” answer. In our family now, “peut-etre” has become the standard signal for being totally and self-consciously clueless.

We’d have to claim to be upscale Bobs from Bamenda. Being scientists gives us lots of contacts. ……

Lodging:

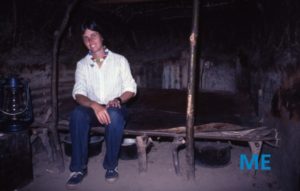

We tried it all different ways. We camped in Masai Mara with lions roaring a few hundred meters away. We camped near the river in Samburu, to awaken to see crocodiles on the bank and elephant tracks around our tent (Jim Beverwyk and Mary Parsaca later reassured us – elephants are very careful. Lions might trip over your tent ropes. Better a 300-pound lion than a 6-ton elephant. Neither was fine with us). We’ve camped on the grounds near the Victoria Falls Hotel, in the magnificent kauri forest in Western Australia, by the hot springs in Waimangu, New Zealand, in tents in the desert of Wadi Rum in Jordan, in a bunkhouse in the remotest south of Madagascar where every star stood out at night as never before in our lives, in a tiny hut in (Zimbabwe?). We slept in a Maasai enkaji of wattle and daub construction, on hides (at least one set of friends said they couldn’t imagine doing that. We replied, “Do you know how much work we had to do to get that privilege, from Maasai friends?).

We’ve spent time in the homes of friends in Japan, New Zealand, Mexico, Kikuyu and Kamba and American families in Kenya, Zimbabwe, Australia, Indonesia, Switzerland, England, Greece, France, Israel, the Galapagos in Ecuador, Canada, Botswana. We’ve been in arranged homestays with Dyaks in Malaysian Borneo, with Viet, Thai, Tai, and Dai in Viet Nam.

Ceremonies:

There are religious ceremonies, there are public ceremonies, there are private ceremonies. Many of them are almost ageless. We’ve been in these unexpectedly. Lou Ellen and I were back in Bali in 2010. We had a Lonely Planet guidebook and a map bursting with promise. One day we laid out a trip that included Tengganan near the southeastern coast. Bali being Hindu there naturally was a temple, a water temple, in fact. Respectfully we entered the temple. We changed into the proper dress of sarongs and no shoes. There was a long, shallow basin with many founts spilling into it. We gazed at it. To our right was a young couple, a robust and handsome young man and a lithe woman. I greeted them in Bahasa Indonesia (not knowing enough Balinese). The man replied and we had a short conversation, when he suddenly invited me to enter the basin with him in his ceremony. We waded the meter or so to one fount. The process involved repeated placing of our heads under the flowing water, and Hindu gestures. I was moved by his acceptance of me. The young woman brought flower petals. At the end, the man asked me in English if I would consider becoming a Hindu. Alas, it was the last we saw of each other.

The Balinese people are very welcoming of people outside their religion and customs to observe their ceremonies, even close up. One morning when we were at Oka Wati’s wonderful small hotel in Ubud we were told that there was a cremation to happen in nearby Gianyar. We drove there and then walked to the field where a large symbolic bull made of a bamboo strip and foam armature with a beautifully painted cloth covering. The body of a deceased, mummified by drying, was placed inside the bull and the pyre was ignited. It was certainly the most dramatic funerary ceremony we have ever seen.

Wanderlust and unusual situations:

Part I: Vince’s longing to be a traveler:

From Berwyn to an Iban Long House on Borneo is a long way – 9,000 miles and 39 years. Berwyn is a working-class suburb of Chicago, and the airplane was a wondrous thing that passed overhead, from Midway airport to who-knows-where. Every day so many planes would pass overhead, and would I ever ride on one, I would ask myself. I collected bubble-gum cards with color pictures of airplanes to savor. I remember the Mooney Mite, and imagining myself floating at the cloud level in one.

My father had Wanderlust and I inherited that and all the accompanying genes. Driving was his passion, as many of his generation of fathers. My mother loved to join in, though later she drew the line at a nomadic life as mobile-home-bound retirees. Eagle River, Wisconsin was the first big deal. Marianne, Nancy, and I all remember lakes, but most of all the Paul Bunyan pancake house where we would have breakfast. Lou Ellen and I have now found cultural icons like this all over the world. In Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea, there is, or was, a tall TraveLodge with the sleepy bear logo. It’s not far from Popeye’s fried chicken, where highlanders in arse grass watched American cartoons. In a remote bar in Bali, near a volcano, Michael Jackson on the TV-VCR as we ate anomalous Western food, with some unsettling translations, such as “toes jam” for “toast and jam.”

People. Part I:

People are fascinating everywhere. It took me some time to find this out in depth. Being ‘smart’ and a science wiz in my early life did isolate me from the social whirl. I had some good friends – like Skipper, whom I could please 30 years later with an account of a Garrett-Beyer steam locomotive that started up in front of us in Gilgil, Kenya, clouds of steam and smoke – Skipper is a train fanatic. Still, I was shy. Now I’m not; I love to make contacts, scientific and personal. It’s even more interesting in a foreign language. One is never truly comfortable, negotiating one’s way to a rendezvous imperfectly defined in a language in which one misses some key ideas now and then. It took six months of living in Montpellier, France for me to spin up to speed in French (but then I was taken as being from the Midi. Nice. There were some hilarious misspeakings on my part, along the way).

On to a tenuous but successful link in a new language. One July afternoon found us in Magadi, Kenya. It’s in Maasai country and has been for centuries. It’s also a company town, of the Magadi Soda Company, which explains the incongruously perfect paved road, certainly the best in Kenya. My Swahili, or Kiswahili to be accurate, was better than Lou Ellen’s, so I went from small shop to small shop,

asking for Mama Sikinan. Manta, her grandson, urged us to visit her. She is family and family is first. She also was the one who had miraculously raised the family fortune that led to Manta being at a high school in Santa Fe, New Mexico. Widowed at about 20, with one son, she faced a life of poverty, but walked over to Tanzania and learned to be a “bush doctor.” I’m ashamed to think what I’d conceived this to be, but I was soon to be corrected. In any event, she became famous and accumulated large herds of cattle and goats…in her son’s name, of course, according to Maasai custom (not so different from Europe a century ago!).

My Kiswahili is rusty, but I remember asking something like

“Habari yako (“Your news?” A way of saying hello). Mama Sikinan

ako wapi?”

A Maasai girl in her early teens pointed to a dusty plot with some bits of grass. There, under a large acacia tree, were about 10 men encircling two women and watching intently. Mama Sikinan, in her seventies then, was bestride a younger woman lying face up on the ground. Simon Tome Rotian Katikash came up to me. I remember that name forever. “Stick around. This will be interesting,” he advised me. Then he regained his place in the circle. Mama prodded the woman’s abdomen with great care a number of times. The woman did not move. Mama reached for a circular bit of tin-can lid and rinsed it in water from a large can. My eyes widened as she sliced ever-so-carefully into the woman’s chest, between two ribs. The woman heaved but made no sound. Mama put the knife down. She then pressed her lips to the incision and sucked. After half a minute, she rose. She spat out a white mass with some blood. She explained her finding in Maa. Simon told me she had diagnosed a fatty cyst, which now lay before us. Mama washed the woman’s chest with water from the can. The woman sat up, took up her robe, and stood up. I awoke from my transfixed state to get Lou Ellen. There had been no time to get her from the rented Land Rover. I have told her the story many times since. It can never leave my memory.

Conversations with the locals – what tourists miss. Part I:

It’s early afternoon on a mild January day. We’ve traversed the forest road to Abong-Mbang in eastern Cameroon. There’s a burly, smiling local policeman – he may just know where we’ll find Shelley Leasia, a friend of Lou Ellen’s first husband. Now, after 34 years, I don’t recall the French we spoke, but he held my hand as he asked many residents about Shelley on our behalf. It does feel odd for an American male to have a man hold my hand so long, but it’s perfectly natural in Africa; join the culture.

The conversations shortly moved on to new dimensions. Here we are now with Shelley and her American Peace Corps colleagues, speaking French with the one French volunteer assigned here. I’m losing the thread. My French is still rusty after 13 years of virtual non-use. I’m not alone in losing track; one by one, the Americans drop out as the Frenchman becomes more voluble and his sentences more elaborate. The last one standing, as it were, listens to our new friend pose a very lengthy question… and covers his final incomprehension with a masterful “Peut-être.” Mental applause circulates around the room.

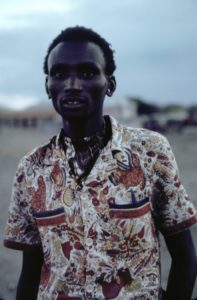

The next day, we’re speaking with pygmies, adapting to life in a village set up for them. Our conversation was mediated by Laurent, Shelley’s Camerooni friend, who translates for us. Oddly, it does not seem odd that we are 5,000 miles from home, in the “jungle,” as it were, speaking with pygmies. We do these things, and we return to our stateside life, changed, but back in our own milieu. It’s odder for the pygmies, and surely staying odd. Missionaries are trying to shift them to a sedentary life. Maybe they have no nomadic life they can ever go back to. What’s happening, and why? I imagine mixed motives of the missionaries – some concern for the welfare of the pygmies, more concern for spreading their own religion.

Culture – history:

Ubirr, Xi An, Bognor Regis, Notre Dame, Hiroshima, Sacsayhuaman, Haida Gwaii – We are drawn to history, cultures, art, nature, meeting new people. When we head for any country, we expect a culture in a number of ways orthogonal to our own, yet also with its citizens sharing universal human values, and it works out that way. For 3, 4, 5, 6 months before a trip we dig into the place we’ll be. Learn the history, learn some of the language, get maps (treasure troves). There are 4,000 books in our house. There’s the Lonely Planet guidebooks, and before them, many old and often quirky titles. There’s Culture Shock {Fill in the country} series to tell us, among other things, what not to do – in Thailand don’t stop a banknote blowing away by stepping on it, for it has the picture of the revered king. There’s the Christian Science Monitor, one of the rare American magazines to even mention a foreign country, and it does so in terms as often bewitching and humane as cautious. We also will talk to anyone about travel. Warrick Silvester came to the Los Alamos Labs from New Zealand to give a lecture and invited us to stay with him and his family at the drop of a hat, and that’s how we ended up learning the Kiwi Grace before meals and “horse bite” teasing. Vince, before his first overseas trip at the ripe old age of 32, talked to A who talked to B who talked to C who finally linked him up with Jim Beverwyk and Mary Parsaca, old hands at Kenya from Peace Corps days, and so ended up forgoing a Sierra Club group trip and going on his own, so fulfillingly. Someone told us about a Maasai student at Santa Fe Prep; he told us we must see his grandmother, Mama Sikinan. “She does bush medicine.” Indeed, surgery in the bush before Vince’s eyes. Stay in a longhouse with Iban people, former headhunters? Yes. Sleep in a Maasai enkaji on hides? Yes. Talk to a caviste in Montpellier to learn about wines and about French ways? Sure.

Cultures of other countries and other regions have expectations of us and we have expectations of them. Asian cultures like drinking to establish trust. In that Iban longhouse, strong arak was always being poured into glasses, but we had learned that it’s polite to pour your new slug into the glass of the person next to you if you don’t care to be drunk.

Adventures and risk:

In a note to my (Vince’s) niece Sue Ferrara, I recollected the adventures we took. Lou Ellen and I look back on some trips and activities we undertook and think, Wow, we did that, and so often? We learned quickly that risks are more projected than real. I went to Kenya on my own in 1977 and “braved” malaria (minuscule risk), wild animals (some close calls), and a very different society with few of the down-home safety nets (but it was a welcoming society or set of societies, as we learned both ways – we had to be the un-ugly American). We traveled together after that in very remote places, often relying on that quintessentially American lifeline, the car and on the widespread, innate good will of people around the world, especially visitors like us who were engaged with them to share their experience with nothing to sell or proselytize. The third time we went to Kenya we had David with us as a babe in arms, camping in Kenya’s game parks or, a month later, walking the streets of Kuching in Borneo or passed among the mamas in a Dyak longhouse. We were well aware of our context, so we were not freaking out at imagined hazards, physical, biological, or human. We climbed mountains higher than those in the lower 48, we rode canoes in the flooded Amazon, we ate street food on six continents (with clear precautions), we drove deserted roads on the coast of Western Australia, we bunked down in a Maasai manyatta, we snorkeled and dived in half a dozen seas. We met the most amazing people. We found Muslims to be the most hospitable and trustworthy people. We haggled for a ceremonial hatchet with a delightful tribesman in Papua New Guinea. We talked with the local people in every one of 41 countries, in English, Spanish, French, some German, and a smattering of languages such as Bahasa Indonesia. Along the way we instilled in David a great desire for travel and social acceptance of people of all types. Lou Ellen likes to recall the time when he was 6 years old that he was trying to tell here which classmate he was talking about. He added more and more descriptors with no luck until he added, “Well, it doesn’t matter, but she’s black!”

More topics to come! How we do photography; Planes; Modes of travel; and more